Lee

Brilleaux - Melody Maker (15 septembre 1984)

Propos recueillis

par Allan Jones et Tom "Vasco" Sheehan © Melody

Maker

An officier & a gentleman

A decade ago, Dr Feelgood came

roaring out of Canvey Island like an R&B hurricane. Ten years

on, Lee Brilleaux, now the only surviving original member, is still

causing maximum havoc throughout Europe. Allan Jones reports from

Holland, Belgium, France and Basildon. Tout guide and photography

: Tom "Vasco" Sheehan.

Brilleaux enjoys a coffee and digestive

The sun

was over the yard-arm, but there was no a sign of the Feelgoods

at the airport bar, where they’d promised to meet us. The

group’s absence was more easily explained than our presence

that morning in Amsterdam. Sheehan and I had turned up on the wrong

day.

Schiphol Airport was a fraught carnival that Saturday morning and

the jostling crowds of Dutch holiday-makers in their satin running

shorts and Nike clogs treading enthusiastically on our toes and

swearing at us in their garbled excuse for a language did nothing

very much to improve the photographer’s notorious temper.

"This is brilliant", scowled

Sheenan, heading for a massive sulk. "What

do we do now ?"

"Pannic ?" I suggested,

not very helpfully in the circumstances. I immediately regretted

my flippancy and offered to stand the smudge a drink, but Sheehan

was having none of it.

"I hate Dutch beer", he

snarled through clenched teeth. I could tell by the wrinkles in

his syrup that he wouldn’t quickly be calmed down. The girl

at the tourist information desk was a little more sympathetic. "Yoo

hef lost all yoor frindz ? This is offal", she smiled

with a motherly concern beaming at us like we were a couple of bedraggled

orphans, tossed into her lap by circumstances probably too tragic

to even contemplate.

"Let us see vot ve can do",

she continued with matronly zeal. "NOW

! Ver are zey stayink, pliss, yoor frindz ? Giff to me the nim und

undress of zeyer hootle and heer I vill lick it oop in my hootle

directory." She brandished a hotel directory, inches

thick. I had to admit that I didn’t know exactly where the

Feelgoods might be staying, wasn’t even sure they were in

the same country, but thought they might be at a hotel called Boddy’s.

She flicked through the pages of the hotel directory ; I smiled

uneasily at Sheehan, failed signally to reassure him that I was

on top of our predicament, would soon see him safely through this

early hitch in the campaign.

"Zer is heer nuzzunk of zat nim",

the girl at the tourist information desk told us, her voice throbbing

with regret. "Yoo are shoor this hootle

iz in Amsterdam ?"

"Well, more or less",

I told her, not sure anymore of anything much. "Ver

zen iz it ? I heff no nim heer zat is Booties. Pliss, yoo vill sink

ver iz zis hootle – yoo heff bin heer beefoor ?"

We had ; once. With Jake Riviera and Carlene Carter, two years ago.

"I know it’s opposite a canal",

I offered, hopelessly vague.

"C’m’ere",

Sheehan glowered, grabbing the hotel directory. He was by now ready

to take the matter in hand himself. He studied a street map of the

centre of Amsterdam. "Right",

he declared. "We’ll get

a taxi to this place ‘ere and I reckon I can get us to Boddy’s

from there." We were in a taxi within

seconds, heading for the centre of Amsterdam. We pulled up outside

a hotel where Sheehan claimed to have taken photographs once of

Tracey Ullman.

"This way, Jonesy",

he barked, slinging his camera bag over his shoulder and waddling

purposefully down the street, into a maze of side-streets, over

bridges that spanned canals like thin, warped spines.

"Down ‘ere",

Sheehan decided, crossing back over a canal vanishing up another

narrow avenue. "I remember

this bar", the photographer decided,

"so it must down here".

And he was off again, determined.

After nearly 40 minutes of this punishing route-march through the

cobbled streets suddenly of old Amsterdam, Sheehan stopped suddenly

at a street corner, pointed across a canal, stood with his hands

on his hips, a proud, steadfast little figure, mightily pleased

with himself. "Thar she blows

!" he announced with a nautical swagger

that quite became him.

And thar she did certainly blow. Boddy’s Hotel ! Otherwise

known as the Hotel Weichman. "Are

we talking walking A-to-Z of Europe or what ?"

Sheehan demanded rhetorically, smug now in his navigational triumph.

"Well done, Vasco",

I muttered spitefully, tottering after the great explorer as he

strode a-bobbing over the bridge toward the hotel, where we found

a contingent of Feelgoods still playing with their breakfasts.

Chris Fenwick, the group’s manager, was there. Three weeks

earlier we’d been drinking in The Oporto and he’d first

suggested this madcap scheme. It was time, he thought, for the Great

British Public to be reminded of the Feelgoods’ line-up had

been together they’s had no substantial press coverage ; mostly,

they’d worked abroad, coining it in on the continent, in the

Far East, Australia. This autumn, however, they were mounting a

concentrated compaign in Blighty ; a 30 – or 40-date tour

- , he reckoned.

They’d signed a new record deal ; by then a new Feelgoods’

album would be out on Demon Records. It had already been released

in Germany, it was called "Doctor’s Orders" and

the krauts were mad for it. He thought I might like it, too ; and

he was right. I did : and liked it enough to sign up for this current

jaunt.

The plan as originally outlined was straightforward, if a little

eccentric. Sheehan and I would fly out to Amsterdam, where the Feelgoods

are still something of a cherished institution, catch them headlining

at an open-air festival in the Vondelpark, then drive across Holland,

through Belgium and France, to Calais. At Calais, we’d hop

a ferry to Dover, ad from Dover we’d drive to Leigh –

on Sea, arriving at about, oh, thought Fenwick, hugely amused by

the entire notion, at about four in the morning. We’d then

put our heads down for a couple of hours, presuming that we’d

made it thus far, before accompanying he group to Basildon –

of all places – where the Feelgoods were headlining a Bank

Holiday Blues and Folk festival organised by the local council.

Like a sap, I fell for it in tumble ; by the fifth round of drinks

Sheehan had also enlisted, thrilled no doubt by the very prospect

of working with men again after all those sessions with chaps in

frocks and make-up that had seemed recently to have taken so much

of his time.

And, so there we were : in the lobby of the Hotel Weichman, with

Fenwick staring, open-mouthed at our premature presence. New Feelgoods’

guitarist Gordon Russsell was with him, so was drummer Kevin Morris.

They looked tanned and healthy after a recent stint at some posh

old gaff on the Riviera. Fenwick popped a boiled egg into his mouth.

We stood there, drained by our exertions, sweating, puffing. "Jones.

Sheehan", he said. "A

day early, and probably thirsty".

Fenwick dabbed at his mouth with a paper napkin. "Lee’s

already in the bar", he said. "I

suppose we’d better join him…"

Lee Brilleaux,

now the only surviving member of the original Feelgoods, looked

like he’d been in the bar for some time.

"Monstrous’ angover,

this morning", Brilleaux snapped,

his voice as raw as stubble. He ordered up brace of beers.

The Feelgoods, we learned, had been in Amsterdam for a week. Based

at the hotel Wiechman, they’d been making regular forays out

into the countryside.

"It’s a damned civilised

country, Holland", Lee told us. "Nowhere’s

more than 150 milesaway, so we can dash out, play a gig and still

be back in Amsterdam for a drink before closing time. Admirable

set-up."

The Feelgood’s Dutch excursion marked the climax to a six-week

tour of Europe that had taken them through France, where hey’d

played at the Mont de Marsan festival. Mont de Marsan, of course,

was the location in 1977 of Marc Zermati’s infamous Punk Festival.

The Feelgoods had headlined that year, crowning it over younger

bands like The Calsh, The Damned, The Jam and The Police. I winced

at the very mention of Mont de Marsan ; as a survivor of that weekend

in 1977, I was still haunted by nightmares of its chaos and excess,

the sheer hysterical pandemonium of those three days in the shadows

of the Pyrenees.

"It was much more civilised

this year", Lee said, reassuringly.

"Remember that old bullring

we layed in that first year ?" I

did, with a clarity that brought me out in a cold turkey sweat.

"They’ve done it up’

andsome. All mods cons, that bullring now. They’ve got a chapel,

an operating theatre, the lot. Very smart. It looked like an abattoir

before, didn’t it ?"

This year at Mont de Marsan, the Feelgoods had been down-bill to

Echo & The Bunnymen, but still turned the crowd, ended up with

a brace of encores and demands for an early return.

"We went on in the rain", Brilleaux explained, trying

to attract the barmaid’s attention for another round of drinks.

"So we got the sympathy vote.

Very nicely played, I thought."

From Mont de Marsan the Feelgood had travelled on the Riviera, where

they’d played a residency in Sete, on the Golfe du Lion, at

a club called Heartbreak Hotel.

"It was an absolute grin",

Fenwick beamed. "The guvnor

said, "Here’s the barn help yourselves."

I said, "I hope you’re

serious, because we are."

"Very generous man"

Brilleaux said, admiringly.

"He was",

Fenwick said. "I could’ve

cried when we left. I just hope he doesn’t go out of business

before we get a chance to go back."

The only aggravation on the entire trip so far had come on the 1500

mile trek back through France, into Holland.

"The roads were packed, right

through France", Brilleaux spat,

"with Frogs in caravans. I

‘ate caravans", he snapped,

and it was obvious that he did. "I

mean, if you can’t afford to go away on ‘oliday and

stay in a decent ‘otel – stay at home. I mean, it’s

just an absolute fuckin’ nuisance to have all these bloody

people draggin’ these fuckin’ bungalows-on-wheels halfway

‘round Europe. They’re just pests, these people."

Lee smacked his glass down on the bar, winced as if he’d just

wrenched his back.

"What’s up ?"

Sheehan asked.

"Must ‘ve pulled a muscle

loading the gear last night", Lee

replied, evasively.

"Bollocks !"

Fenwick guffawed. "It’s

from where you had a go at that bloke at the job last night, nothing

to do with loading any equipment."

"Oh, dear",

Sheeham said admonishingly, trying hard to sound like a man who’d

never got himself into a scrape after a drink too many, "have

a go at someone, did you ?"

"As it happens, yes",

Lee said.

"As it happens, there was a

bit of scuffle last night that needed a bit of quelling…"

Lee drained his glass.

"Right, I think I’ve

got this one under control", he said

of his hangover.

"Anyone fancy a drink ?"

I looked at Sheehan, nodded ; suddenly felt a bit a flashback coming

on.

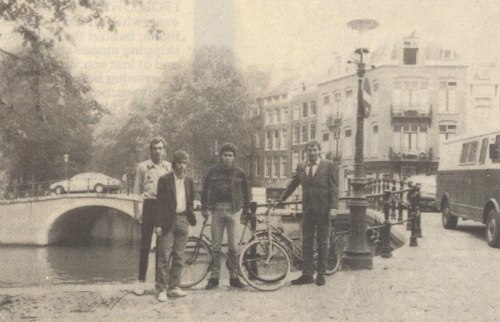

The Feelgoods attempt to sell bicycle to pay for next round...

November,

1974 ; one of those Sundays in Calk Farm when the Roundhouse is

besieged by the Shambling relics of the psychedelic era. Moth-eaten

old hippies in grubby kaftans and tattered headbands are staggering

around the dank corridors, collapsing in piles of flesh and bones

and Moroccan sandles. The air is thick with dope and sweet with

the suffocating scent of patchouli oil.

Most of these squalid wallies are out to see Nektar, a group of

space cadets from Germany. The group on stage right now, though,

is Dr Feelgood, a sharp young outfit, up for the day from Canvey

Island. The Feelgoods are currently moving out of the pubs, into

larger venues ; their first single, "Roxette", has just

been released by United Artists. The group look as lean as whippets,

sound sharp, feverish. This is maximum R&B, played with a devilish

glee, dirty, rowdy, violent.

The stoned-walf of hippies don’t know what to make of them.

The Feelgoods are just too fast, too lively, too noisy, too savage.

Their music is stripped for speed, for action, for nudge and poke

and stab. Then, as now, as aver, they weren’t terribly interested

in taking prisoners.

During one number that afternoon at the Roundhouse, a demented little

toad in a cape scales the stage, starts bawling some incomprehensible

acid rant into a spare microphone. Lee Brilleaux knows exactly what

he has to do.

Stamping out a cigarette, he stalks across the stage and punches

the idiot bastard back into the stalls, is back in front of his

own microphone before the guitarist has completed his scalding,

nerve-searing solo.

This was a group that didn’t fuck around ; that much was clear.

This was also a group ready and able to carve up the polite face

of mid-Seventies rock, shriek at the walls, burn down the buildings.

Their music was urgent, nasty, tough, the very stuff of legend,

an anticipation of the open warfare that would be waged in ’76

and ’77 by the Sex Pistols and The Clash and The Damned and

their punk cohorts, who streamed through the doors the Feelgoods

had already kicked open…

A

decade later, much has changed. Brilleaux fronts a new Feelgoods.

Only fenwick is left to remind him of the original group, their

early days at the Cloud 9 on Canvey, their first forays into London,

at the Tally Ho and the Kensington. Ten long years on from "Roxette"

and "Down By The Jetty" and "Stupidity", Lee

is still there, though the others have long since quit the scene.

There he is now, onstage in some Godforsaken outpost named Bakkeeven,

up there in Friesland in the north of Holland, working the crowd

in a club called De Gearte, winding up the locals with a stream

of invective, pacing impatiently between Gordon and bassist Phil

Mitchell, his hair plastered to his scalp, eyes bulging, fists clenched,

roaring through a selection of vintage Feelgood tunes ("Baby

Jane", "Back In The Night", "She’A Win

Up", "Sugar Shaker") and equally fiery cuts from

the new album, including a blistering "Close But No Cigar",

a brooding "Dangerous" and a ribald version of Gordon’s

"She’s In The Middle".

Any doubts that these new recruits to the Feelgoods’ banner

might not cut it with the dash of their predecessors are quickly

dispelled, these boys are mustard ; the Feelgoods are still the

killer elite of maximum R&B.

Trooping off-stage after their fifth encore, the Feelgoods collapse

into their dressing room, exhausted, all energy apparently spent.

The club owner, delighted, rushes around, pumping hands, slapping

backs, demanding an early return. Lee pours himself a large gin,

gulps it down, harrasses the rest of the band.

"Five minutes", he insists,

"and we’re off".

"What’s the rush ?", Phil

demands wearily, towelling off the sweat from the gig.

"Well", Brilleaux barks, "I

reckon if we put our foot down, we can be back in Amsterdam for

a swift 'alf before they put the towels up…"

Sunday morning

in the Vondelpark. Lee is nursing another serious hangover. The

group want to run through a quick soundcheck before that afternoons

show. Lee is having none of it, however.

"I ‘ate soundchecks",

he grimaces.

"Pointless bloody affaires, waste of time. We’ll

just go on get on with it. What I need is a livener. Anyone fancy

a small coffee and a digestive ?"

Sheedhan and I take a stroll through the park with Lee.

The Vondelpark is a vision of decay. Derelict hippies are stretched

out on the grubby lawns.

"What an ugly bleedin’ bunch",

Lee remarks testily as we step gingerly over the bodies of assorted

flower children, most of them gone to seed ; the washed up debris

of a wasted dream.

"It’s all a bit Glastonburry, this."

Sheehan observes distastefully as we pick our way through a stretch

of market stalls selling worthless hippy ornaments and tacky trinkets.

"What this place needs", Brilleaux

snaps, "is an artillery barrage to liven it up and see

off this shower. Start off with a few motors lobbed in from close

range, follow it up with a couple of Spitfires strafing he gaff

just to create a sense of panic, then send in a hand-picked team

of paras to mop up. Should do the trick."

Lee stalks off ahead to us.

"Glad to see Lee’s in such good mood this morning",

Sheehan says hitching his camera bag over his shoulder, making tracks

in Brilleaux’ furious slipstream.

Lee felt a lot better after his coffee and digestive (Lee’s

"digestive" turning out to be an extremely severe brandy),

and his mood brightened again when we returned to the Vondelpark

to find a massive crowd waiting for the Feelgoods.

"I do believe we’re going to have it off ‘ere

this afternoon", he said cheerfully, changing

into a sharp blue suit.

And they did cracking through another frenetic set, wose highlight

came with Gordon’s punishing guitar work out on the smouldering

threatening "Shotgun Blues".

"Lay’n’genn’men",

Lee announced finally, "thank yew for bein’ a

wonderful audience this afternoon in the Vondelpark. Hope to see

you again soon, either here in Amsterdam or anywhere else in the

world we might meet… This is our last number - 'Down At The

Doctors'"…

Backstage, Lee wasn’t hanging around for the congratulations

of the promoters and the group’s Dutch agent. Everyone wanted

to shake his hand and find out when the Feelgoods would’ve

back, but Lee was hustling everyone onto the ferry back to Blighty.

Lee edged the van through the narrow lanes between the rickety market

ahead was packed with conspicuously glazed locales, stumbling, meandering,

daydream strolling.

"It’s like Mombasa out there",

Lee swore impatiently.

An egg shattered against the side of the van ; Lee was furious.

Dancing in the trees we could see a group of local casualties laughing,

jeering.

"If we weren't in such a hurry",

Lee said, "I’d stop and have a row with that lot".

And then we were through the park gates, hurtling through Amsterdam,

onto the motorway across Holland, into Belgium.

"Are we going to stop at the Belgian border ?"

Phil wanted to know.

"Only if they’ve built a fuckin’ roadblock",

Lee replied, his foot hard down on the accelerator, flist balled

tight around the steering wheel, a determinate look in his eyes.

Roaring

through the night like a hellbound express, I asked Lee why we’d

undertaken such a lunatic drive half-way across Europe to catch

a ferry at Calais when most sensible people might’ve just

trucked comfortably up to the Hook of Holland and hitched a boat

there.

"The Sea-Link ferries at this time of year",

Lee explained, racing past a convoy of caravans whose very presence

on the road appeared to annoy him immensely, "are full

of ‘orrible German tourists with rucksacks who jostle you

at the bar. Ghastly business all round. This way, we miss out on

all that. And, anyway, we miss out on all that. And, anyway, Townsend

Thorensen have ferries goin’ out of Calais…"

So ?

"Well", Brilleaux smirked wickedly,

"me an’ Fenwick have shares in Townsend Thorensen.

Means we can get the van, the equipment and all us lot over for

‘alf price. Very reasonable rates indeed…"

The mind boggled ; the night went on.

High noon in

Basildon. The Feelgoods have just arrived to set up their equipment

for that afternoon’s tow shows.

Evryone’s still shell-shocked after last night’s drive

across Europe.

On stage local cowboy is tuning up for his country and western act.

"If he starts playin’ that banjo I’m going

to have to have a very large gin", Lee snarls.

The last two days have been exhausting ; Sheehan and are about to

peel off, heard for home and geyt pir head down. For the Feelgoods,

however, this is just the start of another week. They’ll have

a few days off, then hightail it to Scandinavia or wherever else

the work is. After 10 years of this kind of punishment, I wondered

what kept Lee going.

"The threat of bankruptcy, mostly",

Brilleaux replied, laughing. "It’s a job and a

way of live, all this, you know. We work hard, we made a decent

living. Simple as that. It’s hard graft, but it’s still

damned good fun, for all that. I’m happy just to be in work.

I mean, there’s four million unemployed. I don’t want

to add to the numbers. As long as someone wants us to put on a show

for them, we’ll be there. I know a lot of band wouldn’t

even have thought of doing what we did last night, but you’ve

got to go for it."

Lee was being called to the soundcheck.

"Soundchecks", Lee groaned.

"They’re the worse part of it all. I ‘ate

‘em."

And with that, he was off, gin in hand : the Chuck Yeager of Rock’n’Roll.

|